IPI special investigation: The application of criminal defamation laws in Europe Germany revealed as leading user of criminal defamation laws among 18 countries surveyed

VIENNA, Sep 15, 2015 – Germany towers over its European Union neighbours when it comes to the number of instances in which criminal defamation laws are applied, the surprising results of an International Press Institute (IPI) special investigation released today show.

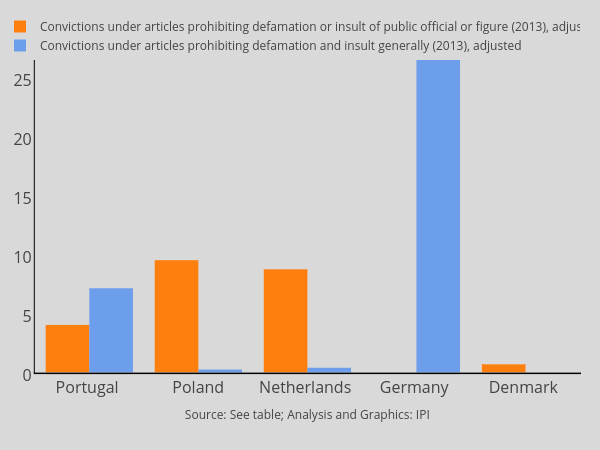

The year 2013 saw nearly 22,000 criminal convictions for insult, defamation or slander in Germany, according to official statistics, more than 29 times as many as in the country with the second-highest number, Portugal. Germany’s place atop the rankings holds firm even when adjusted for population: Germany’s tally of 27.11 convictions per 100,000 residents is nearly four times as great as Portugal, which again holds the second position with an average of 7.15.

IPI has analysed official data on criminal justice for 18 EU countries (see following chart) to provide an unprecedented, detailed picture of the use of criminal defamation laws in Europe. Data collected refer to the use of such laws generally, not specifically against the media; in most cases statistics do not differentiate by the profession of the defendant. The investigation confirms that criminal defamation and insult laws continue to be actively applied in Europe. In 2013, the primary year for which data were collected for comparative purposes, there were criminal convictions for defamation and insult in all but two of the 18 countries surveyed. The exceptions were Denmark and Latvia. View key comparative results (2013) in table form.

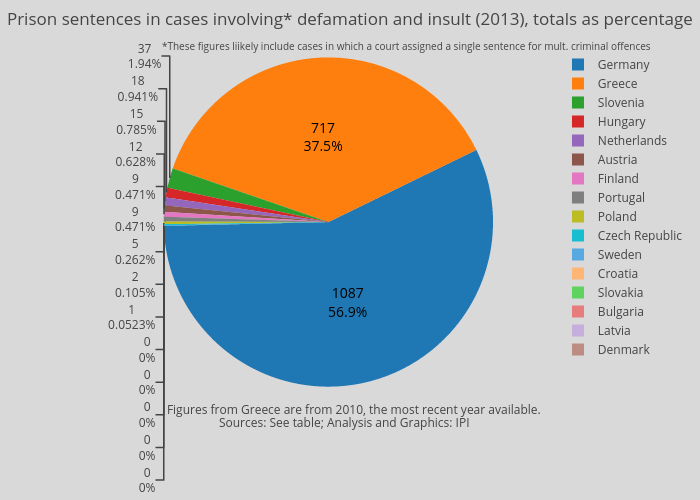

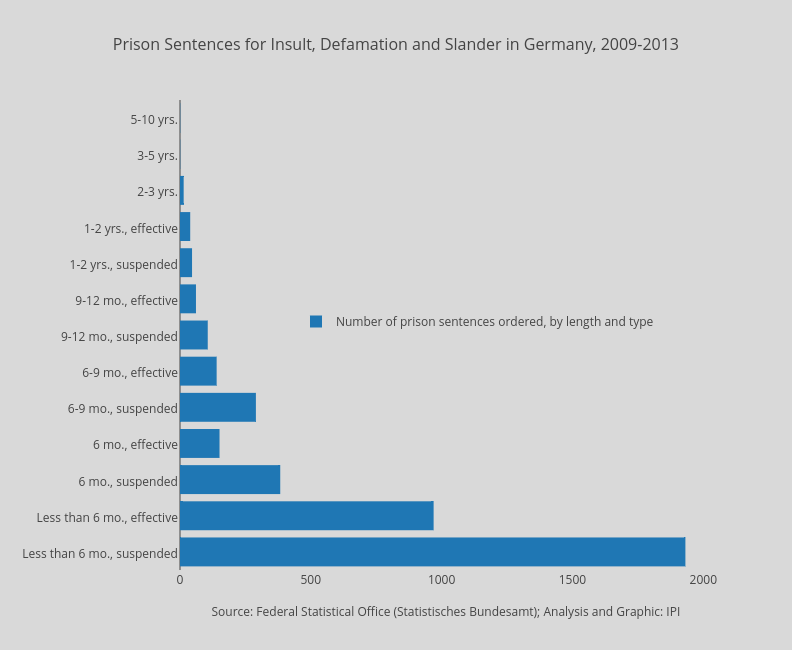

Moreover, the investigation suggests that persons convicted of criminal defamation or insult may face a very real threat of imprisonment. A startling 1,087 prison sentences in cases involving insult, defamation or slander were handed down in Germany in 2013 – 369 of which were unconditional. , however, is the biggest jailer for defamation per capita, with 6.52 sentences per 100,000 residents. Germany is a more distant third, with an average of 1.34.

Data on imprisonment, however, should be approached with caution. National data generally do not indicate whether punishments refer to a single criminal offence or to multiple criminal offences in the case that such offences are tried together and result in a single punishment. Additionally, these data reflect only sentencing and do not necessarily suggest that the prison term was carried out. Under Greek criminal law, for example, all prison sentences for crimes against honour are automatically converted into monetary fines. Additional research at the national level would be necessary to determine the exact contours of the relationship between prison sentences and defamation-related crimes. Nevertheless, statistics indicate that 11 out of the 18 countries handed convicted offenders prison sentences in cases involving defamation and insult in 2013.

Not all data sets analysed by IPI differentiate between suspended prison sentences and those that are unconditional, i.e., prison sentences that must be served. However, the data for Austria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Germany and Slovenia showed the presence of at least one unconditional prison sentence. Germany reported 369. As noted above, the relevance of these figures depends on the extent to which they may reflect cases that combined more than one criminal offence.

Results reveal little correlation between geography and the application of criminal defamation laws. Of the seven countries that show more than three convictions per 100,000 residents in 2013, two are northern European (Germany and Finland), two are southern European (Portugal and Greece*) and three are central European (Hungary, Croatia and Slovenia).

IPI Director of Press Freedom Programmes Scott Griffen, who led the research, said IPI’s investigation added critical quantitative evidence to the debate on Europe’s criminal defamation laws.

“Despite the serious threat that criminal defamation laws pose to media freedom and freedom of expression, 16 out of the 18 European countries we surveyed continue to apply them and have criminal convictions to show for it,” Griffen said. “This situation should be of grave concern to all those concerned with the free flow of information in Europe, given the chilling effect that the use of criminal law to respond to alleged attacks on reputation can have on investigative journalism in particular.

“The data on imprisonment require further research at the national level to determine the extent to which prison terms are associated specifically with defamation offences. But they do raise serious questions. A sentence of imprisonment for defamation contradicts international standards and sets a terrible example for authorities in less democratic countries for whom criminal defamation laws are a convenient tool to punish criticism.”

Although the data analysed did not distinguish between journalist defendants and others, Griffen noted that IPI’s reporting, including its 2014 “Out of Balance” report, has revealed numerous cases in which European journalists have been prosecuted and convicted for criminal defamation. In some cases, journalists have also been sentenced to prison terms.

The investigation’s findings are based exclusively on official statistical data provided by government ministries or national statistical agencies. In some cases, the necessary information was publicly available; in others, it was provided to IPI by official bodies upon request. While a total of 23 EU countries maintain criminal defamation and insult laws relating to private persons, data could not be obtained for five countries – Italy, France, Luxembourg, Lithuania and Malta – which, as a result, were not included in the investigation.

Complete statistics for all countries surveyed, including historical data, can be found on the individual country pages in IPI’s online legal database. Further key findings are highlighted below.

Measuring cases against the media difficult

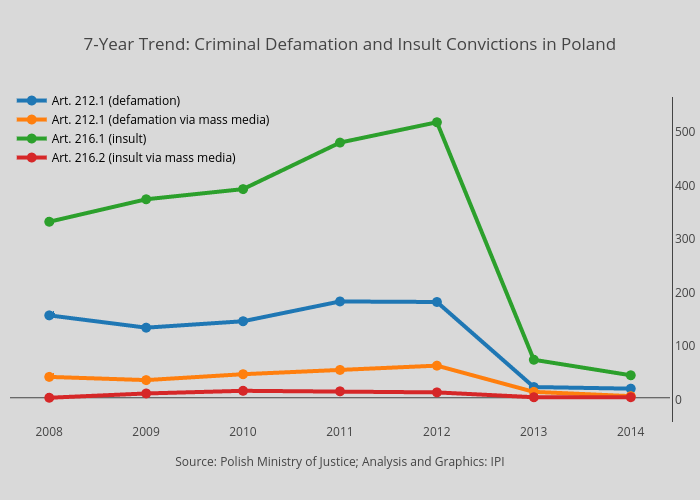

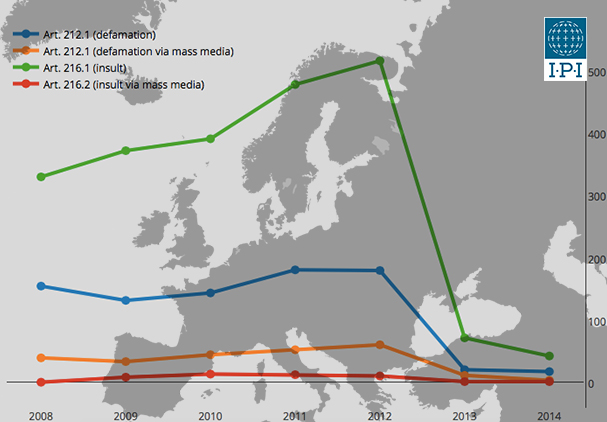

Data reviewed by IPI generally could not be sorted by professional activity of those convicted, making it difficult to ascertain how many convictions involved journalists. But there were a few exceptions. Poland, for example, has a separate provision for defamation committed via the mass media. In 2013, there were 11 and two convictions, respectively, for criminal defamation and for insult committed via the media. A total of five unconditional prison sentences were ordered.

In other countries, punishments increase if defamation or insult is committed through the media or in another public manner. Croatia reported 72 convictions for insult and defamation under such conditions in 2013. Notably, there were no convictions for the country’s controversial criminal offence of “shaming” committed publicly or via the media. Likewise, Portugal registered no convictions between 2010 and 2013 for the crime of defamation or insult committed with publicity.

Obtaining data on the actual application of criminal defamation laws to media requires more in-depth research. One example is an investigation that the Slovene Association of Journalists conducted in April 2015, which IPI published in English this week. The Association surveyed 10 major Slovene media companies on the launching of criminal proceedings against them or their journalists between 2009 and 2014. Results showed that 16 criminal defamation or insult cases were filed against the media during this period.

Increased number of cases involving public officials

Troublingly, the investigation revealed that criminal provisions punishing defamation of public officials yield far more convictions than their counterparts related to criminal defamation and insult generally.

For example, while Poland saw “only” 103 convictions for defamation and insult in 2013, it registered a whopping 3,666 convictions – 35 times as many – under Criminal Code Art. 226.1, which prohibits insulting public officials. Likewise, while Polish courts handed down a relatively restrained five suspended prison sentences in cases involving defamation or insult against private persons in 2013, statistics show 1,481 prison sentences were ordered in cases involving violations of Art. 226.1. Of those, 220 were unconditional sentences.

Similarly, the Netherlands reported 70 criminal convictions under general provisions for defamation, libel or slander (Criminal Code Arts. 261-262) in cases that came before a judge. There were 15 prison sentences in cases involving these provisions. But there were 1,490 convictions and 255 prison sentences for defaming or insulting a public authority, public body or public official, including insult of police officers, under Art. 267. (Again, it is not known how many of these sentences are compound, i.e. reflecting a sentence for multiple crimes.)

On at least this one measure, Germany turned in a relatively positive performance, reporting six criminal cases and zero convictions under Criminal Code Art. 188, which punishes defaming a person “involved in the popular political life”.

The U.N. Human Rights Committee states clearly in General Comment 34 that laws “should not provide for more severe penalties solely on the basis of the identity of the person that may have been impugned”, as is presently the case in Poland, the Netherlands and Germany, among others. Moreover, the view that public officials must accept a higher degree of criticism than private persons is a staple of the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights.

Ghost laws

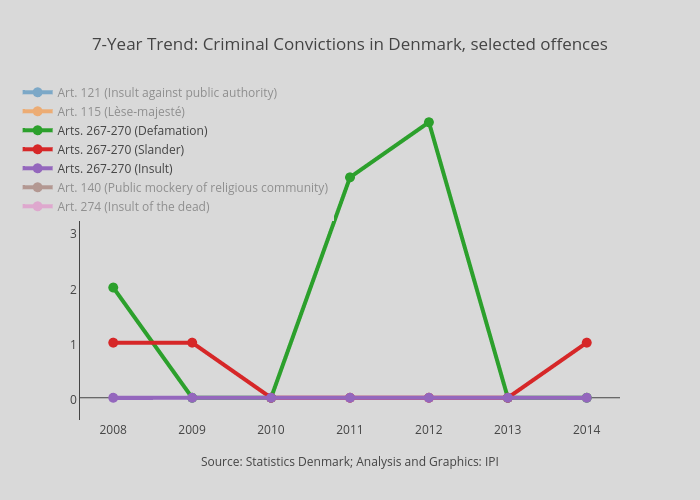

While the results of IPI’s investigation are notable for the extent to which criminal defamation laws continue to be applied in the EU, two of the 18 countries surveyed, Denmark and Latvia, reported no criminal convictions for defamation in 2013. But what is more notable is that between 2011 and 2014 there was just one reported instance of criminal defamation being used in Latvia; a case that did not lead to a conviction.

Denmark’s statistics are even more positive. There has not been a single case for criminal insult brought in Denmark since 2007 and courts have handed down just 14 convictions for criminal defamation or slander in that same period. However, there were 42 convictions for insulting a public official in 2013 alone and 274 convictions for insulting a police officer.

Five additional countries had fewer than 100 convictions per year. Slovakia (eight) and Bulgaria (10) were the next-most-sparing in convicting their citizens of criminal defamation in 2013.

Griffen commented that it was “puzzling that criminal defamation and insult laws that have obviously become dormant still remain on the books in countries like Denmark and Latvia,” noting that Latvia in particular had made significant progress toward repealing criminal defamation without taking the final step. “Not only are these laws clearly unnecessary, as long as they remain part of the legislation they are setting a poor precedent for other countries both in the EU and further abroad,” he said.

Blasphemy laws

IPI’s investigation also sheds light on the use of blasphemy or religious insult laws, which remain widespread in Europe. IPI obtained data on the use of blasphemy and religious insult laws in five of the 14 EU countries where they remain on the books. In Denmark, where the government earlier this year decided against repealing criminal blasphemy, there were no cases, much less convictions, between 2007 and 2014. Austria reported no convictions in 2013.

Finland did not have any blasphemy convictions between 2011 and 2014, although an average of four cases were reported to the police annually between 2006 and 2014. In Germany, 25 blasphemy cases were brought before criminal courts in 2013, leading to 12 convictions, and involving one suspended prison sentence and 11 criminal fines. I

n Poland, where a constitutional challenge to the blasphemy law is currently underway, 2014 saw four convictions involving three suspended prison sentences and one sentence of temporary deprivation of liberty. Statistics show an average of seven blasphemy convictions per year between 2008 and 2014.

*Data for Greece refer to the year 2010, the last year in which the relevant statistics are available, according to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, which provided IPI data on Greece upon request.